Agincourt took place in 1415 CE and was part of the Hundred Years' War,

which was fought mostly between England and France.

King Henry V of England had invaded France and was pillaging extensively to weaken his enemy.

Edward senior and junior had done something similar in the previous century at Crécy and Poitiers, which they won,

in a large part due to the devastating fire of their longbowmen.

Agincourt had all the aspects of a rematch: again the English king had many longbowmen in his army,

again the French forced him to battle and again he was confronted with a numerically superior French army,

made up of mostly powerful knights.

Henry and his army had landed in Normandy and captured the port of Harfleur after a siege that took more than a month, far longer than they had hoped for.

It was already late in the campaigning season and the army had suffered many casualties from disease.

But Henry did not want all the money that he had spent on the expedition to go to waste and moved on to Calais, trying to provoke the French.

The latter had raised an army, yet were too late to save Harfleur.

Finally they moved to block him.

But the two forces maneuvered around each other for two weeks, the French waiting for reinforcements and both trying to reach a good location.

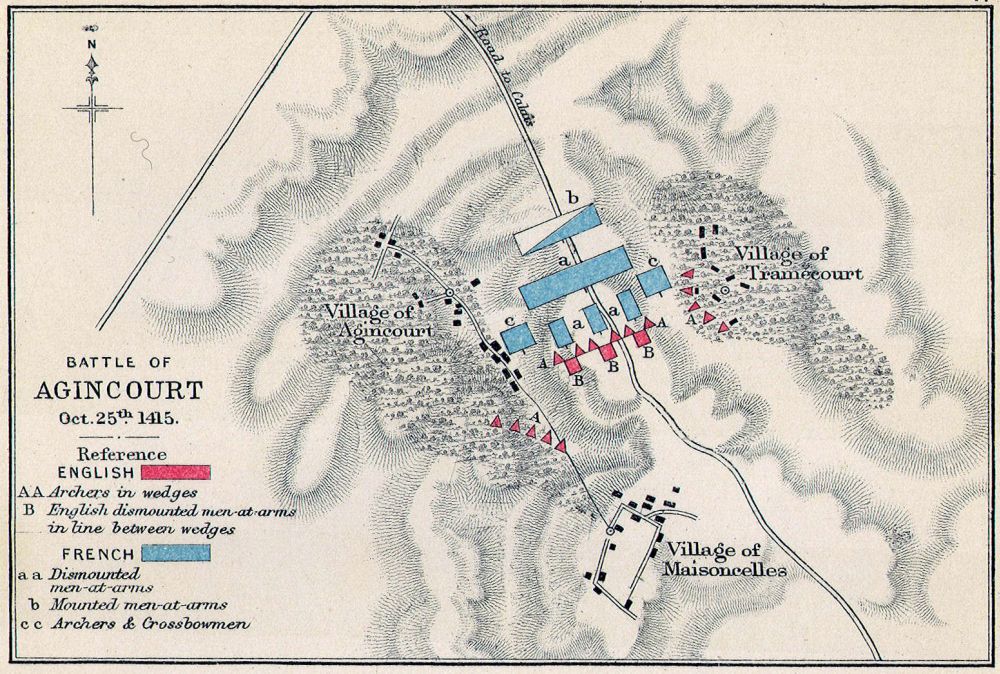

On the 25th of October Henry, whose army was now even more riddled by disease and hunger, decided to force battle between Agincourt and Tramecourt.

Historians have debated a lot about the size of the armies.

It seems that after his pre-battle losses, Henry had some 6,000 - 8,000 men left; 80% archers and 20% men-at-arms.

The French had about three times more fighters, maybe four times more if all half- and non-combatants and support troops are counted.

About 10,000 were men-at-arms, the rest crossbowmen, archers and other light troops.

The English put their men-at-arms in the center and their archers on the flanks, partially shielded by the trees.

There also were some archers in the center, protected by sharpened wooden stakes that had been planted in the ground.

There were only enough men for a single line.

The French nobility were itching to fight their hated enemy.

There were drawn up in two or three lines.

Supporting infantry, archers and crossbowmen were moved to the rear, because the passage between the forests was too cramped to deploy the entire army in a wide front.

This effectively put them out of action, but the French counted on the power of their cavalry.

In the early morning, not all French troops had arrived and for about three hours after sunrise nothing happened.

Henry realized that he could not wait forever and decided to take the initiative, which was risky.

He ordered his men forward, taking care to reposition the wooden stakes also.

Then he let his archers loose some initial volleys.

The French reacted with a disorganized charge.

They could not outflank the English because of the woods and could not quickly get past the stakes.

Their heavy armor protected them well from arrow fire except at very short ranges, but they had many unarmored horses shot down from under them.

The charge broke and men-at-arms on foot took over.

They moved across farmland, recently ploughed and soaked by rain, so it had become a muddy quagmire.

Now their heavy armor became a weakness.

Men struggled to move forward, meanwhile being peppered with arrows, also at close range.

When the English archers ran out of arrows, they switched to swords, axes and mallets,

and engaged in hand-to-hand combat.

Unencumbered, they moved much more nimbly and killed thousands of exhausted enemy men-at-arms.

French reinforcements moved in from the rear, but compressed their front ranks because the battlefield narrowed there.

They became packed so tight that the men had no space to wield their weapons properly.

Many actually were trampled or suffocated in the throng.

Still, they managed to briefly push the English back a little.

Then Henry ordered a counterattack that shattered them.

Thousands were killed or taken prisoner.

The only French success was an outflanking attack on the English baggage train, which achieved little except make the English anxious.

Though they were winning the battle, they considered that French reserves would mount a second attack.

King Henry was afraid that when that happened, the large number of French prisoners would turn against him and ordered them to be executed.

His men-at-arms stood apart, but the archers had no qualms about this bloody business.

This brought the total French losses to about 7,000 - 10,000 plus 1,500 nobles captured but not killed.

The English suffered only a few hundred casualties, possibly as few as 100.

Though sometimes acclaimed as another triumph for the longbow, it was the narrow battlefield, the muddy ground and the grave French tactical blunders that decided the battle.

The English had again won a stunning victory, however its effect on the war was small.

It did weaken the French and made a follow-up invasion two years later much easier, allowing Henry to occupy Normandy.

War Matrix - Battle of Agincourt

Late Middle Age 1300 CE - 1480 CE, Wars and campaigns